Grand corruption and the authoritarian turn

If incoming governments in liberal democracies wish to use public contracts to benefit those loyal to them, they face institutional constraints. To implement corrupt procurement strategies they would need to sabotage these checks and balances. By comparing procurement data from Hungary and the UK, Liz Dávid-Barrett and Mihály Fazekas can identify the relative effect of such anti-democratic institutional changes, as seen in Hungary, on government patronage.

Is liberalism really dead? In his recent interview with the FT, Russian President Vladimir Putin suggested that it is, and he seems to have a growing fan club of authoritarian leaders around the world ready to declare their allegiance to the illiberal cause. Hungary’s Orbán, Turkey’s Erdogan, and US President Trump are perhaps the most devoted, but Duterte in the Philippines and Bolsonaro in Brazil have also shifted their political systems systematically away from liberal democracy and towards authoritarianism.

They like to portray this as a new and noble battle of ideology. But is it, really? In our new paper Grand Corruption and Government Change: An Analysis of Partisan Favoritism we argue that when incoming governments set about dismantling democratic institutions, in particular those that are supposed to check executive power, they are simply seeking to gain – and maintain – control over economic resources such as government contracts. That control, in turn, helps them stay in power, and cements their opportunities to steal more in the future.

The idea of ‘machine politics’ is not new. Politicians have long abused their power to corruptly allocate state resources to cronies, on the expectation that the ‘lucky’ recipients will pay back – either in party or campaign donations, or blatant personal kickbacks. However, in this paper, we develop theory about how they manipulate public procurement to these ends and showcase a new methodology for estimating how much they do it.

We build on a core argument in the corruption literature, elaborated eloquently byAlina Mungiu-Pippidi, that the amount of corruption in a given polity depends on the balance of opportunities and constraints. Institutions matter, in other words. Hence we compare two countries where the strength of institutions differs: the United Kingdom, whose democratic institutions have been consolidated over centuries, and Hungary, where democratisation is relatively recent and fragile.

Moreover, we focus on what happened when there was a change of government, in both countries, in 2010. In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz won a two-thirds majority, while in the UK, David Cameron headed up a new Conservative-Liberal Democrat government. If procurement markets were open and competitive, then a change of government should not make much difference to which companies win government contracts – holding spending priorities constant. But if the incoming government abuses its power to favour allies, the pattern of winners and losers will change.

How do political elites use their power to facilitate partisan favouritism? In public procurement, the opportunities and constraints for corruption are shaped by three spheres of institutions. Corrupt political elites ideally wish to control all three.

First, they seek to influence the formation of procurement laws and rules. To control who gets contracts, it’s best to change the law – to make it easier to avoid using competitive procedures, or to ensure that procurement is not very transparent.

Second, they might try to influence any stage of implementation: the tendering process offers many opportunities for tinkering. If the public official in charge of writing the specification is a loyal appointee, for example, his patron can lean on him to write that spec with very narrow terms, so that only a favoured company can win. Alternatively, the party can suggest a particular technical consultant to use, or ensure that the call for tenders is only open for a short time, so that companies without an advance tip-off have no time to prepare a bid.

Third, corrupt elites need to ‘take care’ of the accountability institutions, which might otherwise detect and question irregularities. In a functioning democracy, the threats to corrupt elites are many: the parliamentary opposition, the courts, the supreme audit institution, the parliamentary public accounts committee, the competition authority and ombudsman, and indeed civil society watchdogs or the media. The real professionals of state capture then, also need to sabotage these checks and balances, so that they can reap the spoils undisturbed.

In Hungary, the Orbán regime faced constraints on its ability to manipulate the first sphere of institutions, because the EU directive on public procurement sets the main parameters of the law. But Orbán had many opportunities to influence the second and third spheres, to control the implementation of procurement, and to disable the checks and balances. He did this largely through patronage power, appointing loyalists to the constitutional court, budget council, competition authority, and the public prosecutor’s office, among others.

In the UK, the institutional defences against corruption were stronger when the Cameron-led government came to power in 2010. There is little scope for political appointments to the UK civil service, the Public Accounts Committee in parliament is very active, and the media free. Cameron did close down the Audit Commission, it is true, and this has undermined the accountability of public bodies, particularly local government. But this was, it seems, largely borne of austerity concerns, rather than part of a grander plan.

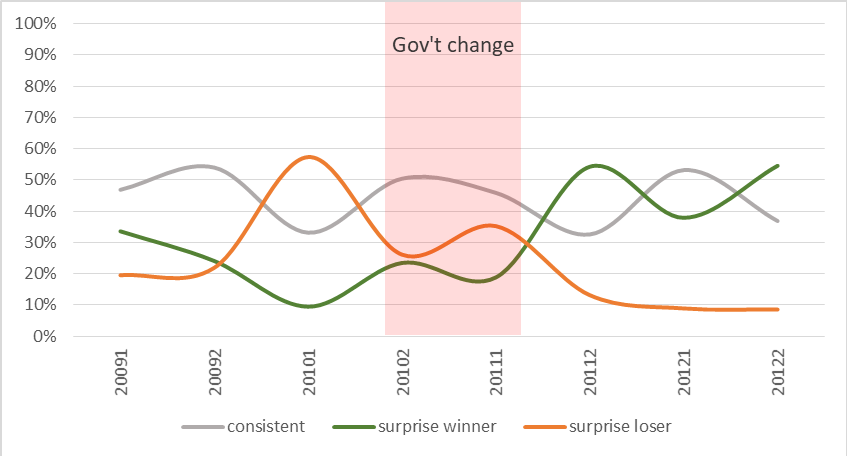

What difference then, did the institutions make? Using a new methodology to analyse large procurement datasets, we examined companies’ performance on procurement markets and whether the value of contracts won is influenced by the change in government. We found that in Hungary some companies that had secured a lot of contracts before the change were largely unsuccessful after the elections; others had barely won contracts under the previous government, yet were suddenly successful afterwards (see Figure 1). We accounted for changes in spending priorities, and the effect remains.

Figure 1: Combined market share of supplier groups, Hungary, 2009–12

For these ‘surprise winners’ and ‘surprise losers’, we also analysed ‘red flags’ in the tendering process, to gain a deeper understanding of the conditions under which they win contracts and check for evidence that the implementation process had been corrupted. From this, we built a Corruption Risk Index (CRI). By cross-checking these two indicators, we constructed a measure of partisan favouritism. In Hungary, we found that such partisan favouritism accounts for 50–60% of the central government procurement market; in the UK, only 5–10%.

In this comparative analysis, the UK is cast as a model of liberal democracy, at least relatively speaking. Britain’s healthy accountability ecosystem seems to be successful in constraining partisan favouritism, but 5–10% of contracts look to be high-risk, even then. This raises questions about the record of the UK’s experiment with outsourcing, concerns not quelled by recent scandals – including the letting of a large contract to the inexperienced Seaborne Freight, the collapse of Carillion and troubles at Interserve.

Governments that centralise power or sabotage checks and balances might claim to be motivated by commitments to law and order. But their behaviour is consistent with another logic: they are abusing their power to create more efficient ways to steal from the state.

This blog was originally published here on the Democratic Audit blog. It draws on the authors’ article ‘Grand corruption and government change: an analysis of partisan favoritism in public procurement’, published in the European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research.